How to Calculate Bitcoin Mining Profitability

Published

22.3.2022

Learn the key factors that influence bitcoin mining profitability and how to calculate them simply.

Table of Contents

Calculating potential Bitcoin mining profitability can be complicated. Deriving a precise number of expected mining revenue and profit requires more data inputs than most people realize. And correct estimations are essential to successful mining at any scale, small or large.

The Braiins mining profitability calculator is designed to support all the necessary inputs for accurate revenue determinations, but for some miners, managing almost two dozen different data fields can be overwhelming especially if it’s the first time a miner is sitting down to run the numbers on their current or future operations.

This article is written as a companion resource to the profitability calculator. Each of the data points available on the Braiins calculator are explained so miners understand what they represent, how to find the data needed for each field, and how to correctly calculate their own mining profit projections.

Time

One of the first and most simple inputs is the timeframe for measuring revenue and profitability. The idea that Bitcoin incentives long-term planning is especially true in mining. Focusing on longer time periods is a more common strategy instead of mining with very short-term profit expectations. Set the range on the Braiins calculator for whatever timeframe is appropriate, between 6 and 60 months.

Bitcoin Price

This metric is also simple and easy to enter. Input the current bitcoin price based on the number displayed by whatever exchange a miner prefers to use or a data aggregator like OnChainFX. Expected future changes in bitcoin’s price are input in another field explained later in this post.

Network Difficulty

Input the current network difficulty level to this field. Expected future changes in bitcoin’s mining difficulty are input in another field explained later in this post.

See current difficulty level on the Mining Insights dashboard.

Hashrate

Hashrate is a value derived from the estimated amount of hashes being generated to solve new blocks. Every make and model of mining hardware has a factory estimated hashrate in the product details. Hashrate is generally measured in terahashes per second (TH/s). Find the hashrate for whatever machines are (or will be) operational, and sum the total hashrate for all operational machines. Enter the value in the Hashrate field.

See historical hashrate data on the Mining Insights dashboard.

Consumption

Power consumption is one of the most important data inputs for any mining operation’s profit calculations, and unlike other data, it’s relatively easy to predict although it’s not a fixed number. Miners usually measure their power consumption in watts (W) per hour (W/h) or kilowatt hours (kWh). One kW equals 1,000 W. Every bitcoin mining machine specifies its factory estimated power consumption in the product details, but the real number can fluctuate. Through normal use, power consumption can increase slightly over time or it can change significantly by choice of the operator when using tools like Braiins OS firmware.

Find a machine’s estimated power consumption in the product details and, for miners operating more than one machine, simply sum the total expected consumption for all operational machines and, if appropriate, account for increases from overclocking with custom firmware.

Electricity Price

The cost of power is one of the data points miners care about most, and electricity prices can vary significantly across different geographic regions. Prices can also vary over time unless a miner secures a power purchase agreement with future power price predictability. Even without that agreement in place, for the purposes of estimating future revenue, a miner can generally use their current power price for future projects. Consider also slightly adjusting power prices up and down to see its effects on future profit.

Block Subsidy

The number of new bitcoins created when each block is mined is the block subsidy. This number changes after each halving event, which takes place once every four calendar years, approximately. For most revenue calculations, adjust the block subsidy if the model is extended beyond the date of the next halving. Otherwise the current block subsidy can be used.

Pool Fee

Fees can vary significantly across different pools, but rarely do pool fees rarely change, or at least change significantly. Compare fees across different pools by substituting them into the Pool Fee field and see the effect on long-term profitability.

See Braiins Pool mining fees here.

Average Transactions Fees

The block subsidy is only one part of the full block reward paid to miners who win each block. Transaction fees for spends included in the block are also paid. Like price and hashrate, transaction fees paid per block vary significantly over time as network use and spend sizes vary.

See average fees per block for the past 2016 blocks (14 days) on the Clark Moody Dashboard.

Other Fees

Additional costs for custom firmware, hosting services, management fees, revenue sharing, or other operational expenses should be summed and entered into the Other Fees field.

Difficulty Increment

Percentage increases of difficulty per year should be entered here.

Difficulty determines how much computing power is required to mine new blocks. Changes in difficulty levels result in changes for how many hashes must be statistically generated to find a valid Bitcoin block. Higher difficulty means more computing power which ultimately means more power consumed by miners, increasing operational costs. Difficulty is measured in arbitrary “difficulty units,” meaning the number is relative. When attempting to accurately estimate revenue, understanding the long-term trajectory of mining difficulty is essential.

Each year difficulty changes approximately 24 times (twice per month), so the percentage increase would reflect the total change from the first adjustment to the last over that period. For example, the average increase of mining difficulty over the past 5 years is 6% monthly, which equates to roughly 100% per year.

See historical difficulty data on the Mining Insights dashboard.

Price Increment

Like Difficulty Increment, this field should contain the expected annual increase for bitcoin’s price. Bitcoin’s price is difficult to predict, so consider different bullish and bearish scenarios with the number entered into the calculator price field. Modeling profit with different price levels over long periods of time helps miners to better understand different ranges of profitability. Miners can also use long term price averages to calibrate their expectations of revenue and profit using more general historical price tools (e.g., 200-day moving average).

Capital Expenditures (CapEx)

Capital expenditures are funds spent by an entity to purchase, replace, upgrade, or otherwise manage physical assets (e.g., mining machines, facilities). Common CapEx fund uses can vary significantly in type and amount across different mining operations, but common expenditures in mining include:

- Buying ASICs and PSUs;

- Constructing, remodeling, or maintaining a mining facility;

- Cooling equipment (e.g., HVAC or immersion tanks);

- Compliance costs.

Sum these costs and enter the final number denominated in dollars in the CapEx field. And even if a complete CapEx cost analysis isn’t available, estimates are still valuable for modeling the effect of expected expenditures on long-term mining revenues.

Monthly Operating Expenses (OpEx)

Operating expenses are typically recurring or cyclical costs independent from mining revenue that maintain the operation. Since electricity costs are already entered in an earlier field, the sum of expected monthly OpEx does not include power costs for miners in the Braiins calculator. Examples of common OpEx funds for miners include:

- Salaries

- Site Security

- Insurance

- Taxes and legal fees

Initial Hardware Value

The data input for the value of mining hardware field comes from simply summing the total purchase price of hardware purchased, or in the case of a miner that has not yet bought machines, estimate the current market value of mining hardware based on the prices listed by manufacturers or hardware resellers.

Hardware Appreciation or Depreciation

This input represents the annual percentage change in the value of a miner’s infrastructure. The value of physical assets like mining machines changes over time, and appropriately depreciating hardware over time – especially as newer and more efficient models enter the market – is an essential calculation for any mining operation, regardless of size. Talk with a tax consultant to understand more details about how to accurately depreciate hardware.

Initial Infrastructure Value

Besides the mining machines, a mining operation also includes a variety of other valuable assets, including land, containers, buildings, cooling equipment, and more. Enter the dollar-denominated value of these assets excluding the value of the actual mining hardware.

HODL Ratio

This input is one of the most important advanced options because it represents how much of the newly mined bitcoins a miner plans to hold. Most miners sell some portion of their revenue to cover operating costs. But it's common to hold some portion of mined Bitcoin on their balance sheet, giving them exposure to potential price appreciation.

HODL ratio is directly dependent on the price increment factor and impacts long-term profits as the price of bitcoin fluctuates. Enter the expected HODL ratio as a percentage. For example, a miner that does not sell any bitcoins has a HODL ratio of 100%. A miner that sells most of their bitcoins could have a HODL ratio of 25%.

Discount Rate

The discount rate is an interest rate used to determine the present value of future cash flows. This helps determine if future cash flow from a mining operation will be worth more than the capital spent to fund the operation now. A non-zero discount rate will not impact the data series visualized on the mining calculator, but the calculator’s backend calculates Net Present Value (NPV) and includes this value in the CSV file download.

What if some data is missing?

A useful mining revenue model doesn’t have to include data for every input described above. But mining operations that are missing several inputs should consider why chunks of data are missing, since most of the fields represent information that should be readily available to most miners.

Still, models are estimates and will not be severely impacted by entering roughly calculations or estimated inputs. After all, every miner produces bitcoin at slightly different costs across a host of variables. Apply common sense and careful estimations, and the resulting revenue model should be sufficiently reliable to guide a mining operation’s future planning.

Final thought: There's no fixed cost for mining bitcoin. The real cost for each miner depends on over a dozen variable data points.

Categories

Be the first to know!

Most Recent Articles

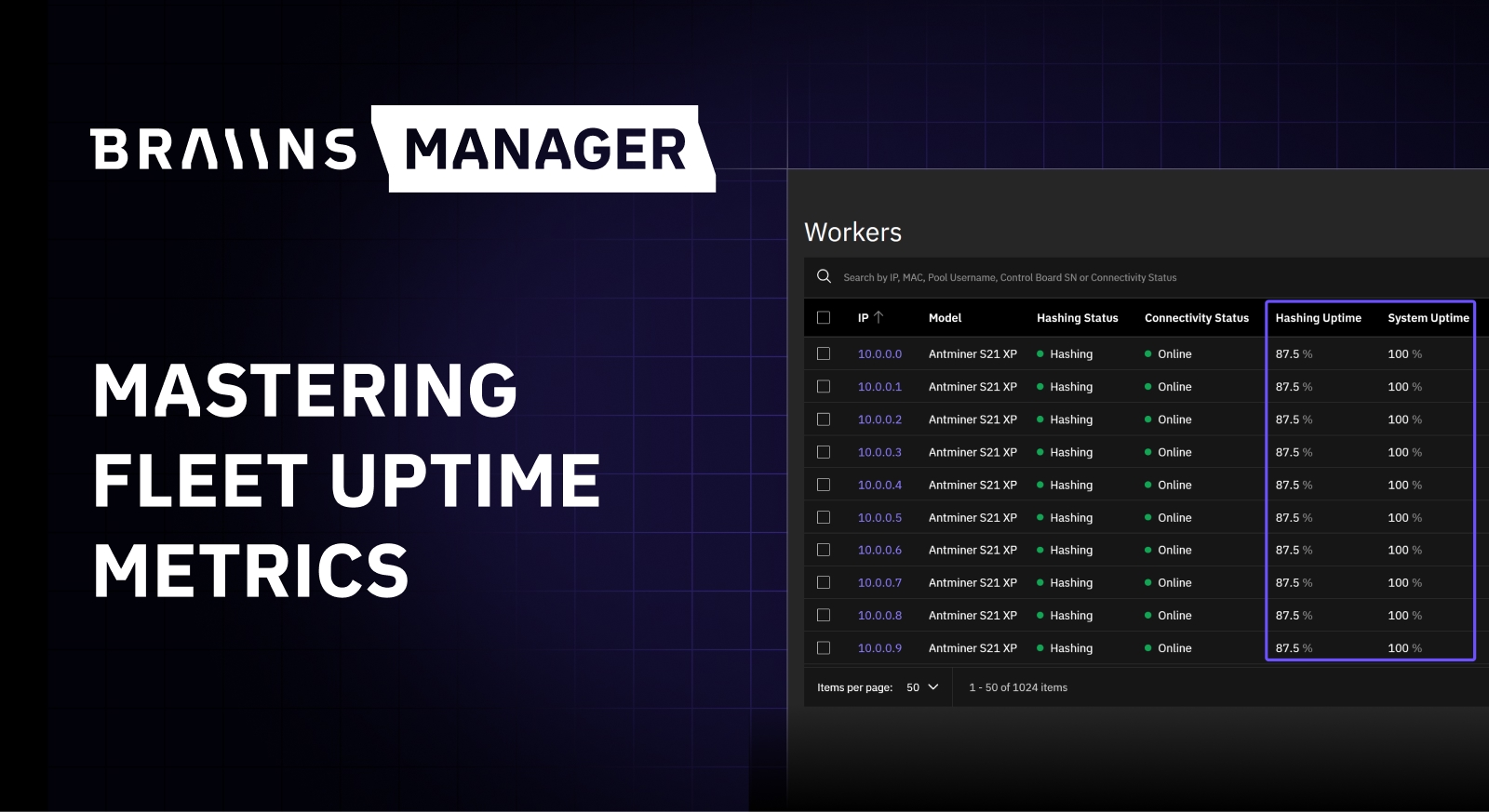

Beyond 100%: Mastering Uptime in Modern Bitcoin Mining

16.2.2026

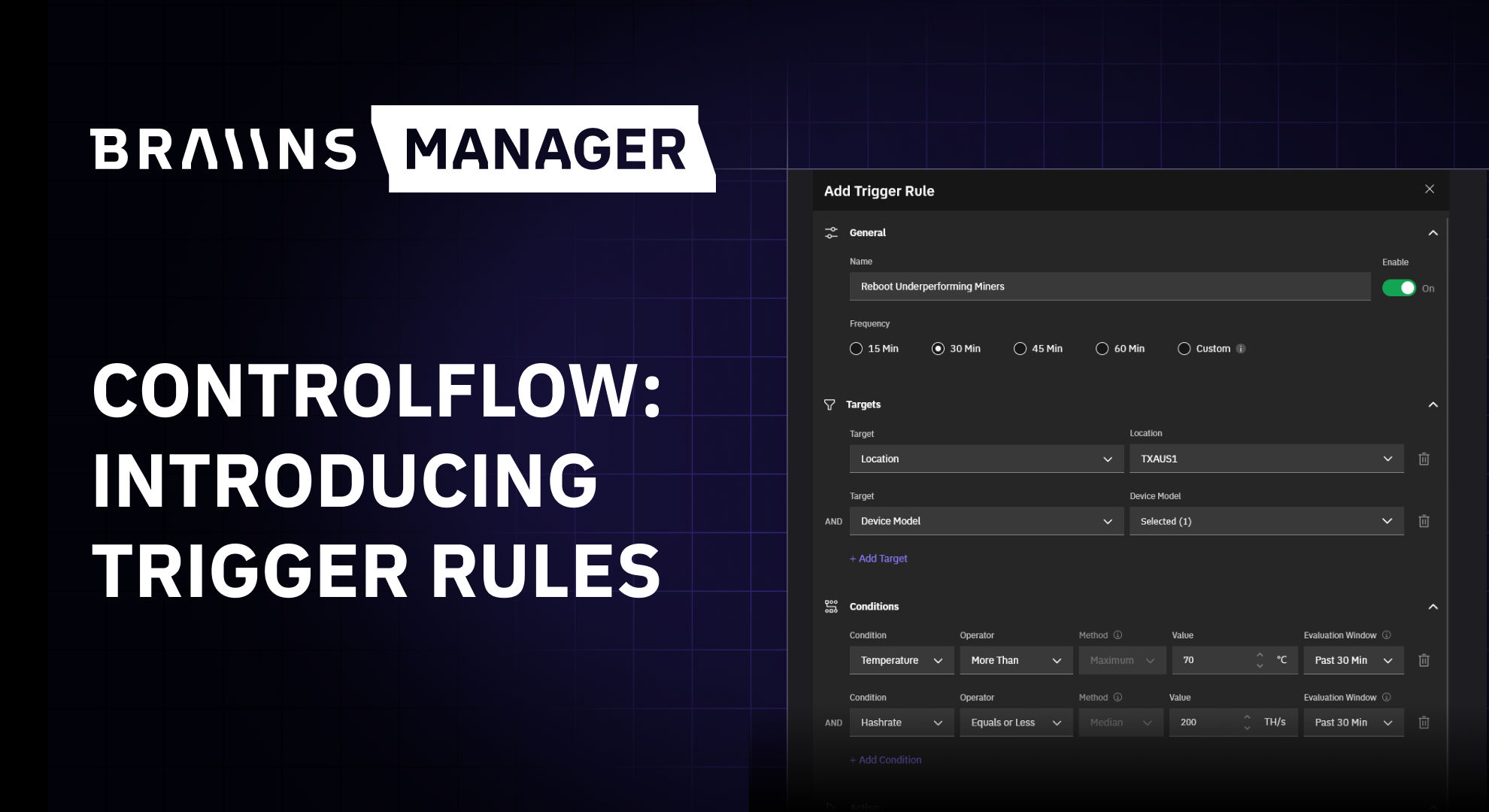

Controlflow Update: New Trigger Rules

21.1.2026